23 Black Rat

MUS RATTUS.--LINN.

[Rattus rattus]

BLACK RAT.

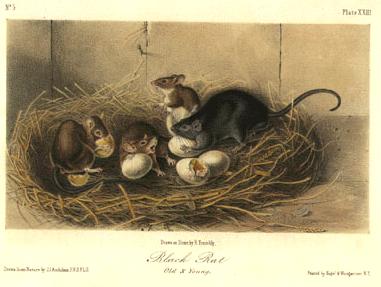

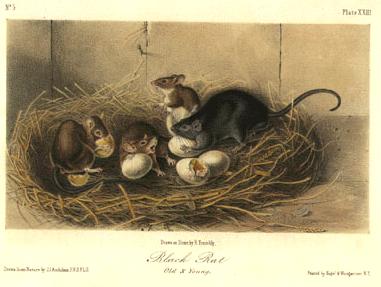

PLATE XXIII.--OLD AND YOUNG, OF VARIOUS COLOURS.

M. cauda corpore longiore; pedibus anterioribus ungue pro pollice

instructis; corpore atro, subtus cinereo.

CHARACTERS.

Tail, longer than the body; fore-feet, with a claw in place of a thumb,

bluish-black above, dark ash-coloured beneath.

SYNONYMES.

MUS RATTUS, Linn., 12th ed., p. 83.

MUS RATTUS, Schreber, Saugethiere, p. 647.

MUS RATTUS, Desmar., in Nouv. Dict., 29, p. 48.

RAT, Buffon, Hist. Nat., vol. vii., p. 278, t. 36.

RAT ORDINAIRE, Cuv., Regne Anim., p. 197.

BLACK RAT, Penn., Arc. Zool., vol. i., p. 129.

ROLLER PONTOPP., Dan. i., p. 611.

MUS RATTUS, Griffith's Animal Kingdom, vol. v., 578, 5.

MUS RATTUS, Harlan, p. 148.

MUS RATTUS, Godman, vol. ii., p. 83.

MUS RATTUS, Richardson, p. 140.

MUS RATTUS, Emmons, Report on Quadrupeds of Massachusetts, p. 63.

MUS RATTUS, Dekay, Natural History of New-York, vol. i., p. 80.

DESCRIPTION.

Head, long; nose, sharp pointed; lower jaw, short; ears, large, oval, broad

and naked. Whiskers, reaching beyond the ear.

Body, smaller and more delicately formed than that of the brown rat;

thickly clothed with rigid, smooth, adpressed hairs.

Fore-feet, with four toes, and a claw in place of a thumb. Feet,

plantigrade, covered on the outer surface with short hairs. Tail, scaly,

slightly and very imperfectly clothed with short coarse hairs. The tail becomes

square when dried, but in its natural state is nearly round. Mammae, 12.

COLOUR.

Whiskers, head, and all the upper surface, deep bluish-black; a few white

hairs interspersed along the back, giving it in some lights a shade of

cinereous; on the under surface it is a shade lighter, usually cinereous. Tail,

dusky; a few light-coloured hairs reaching beyond the toes, and covering the

nails.

DIMENSIONS.

Inches.

Length of head and body . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Length of tail . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 1/4

HABITS.

The character of this species is so notoriously bad, that were we to write

a volume in its defence we would fail to remove those prejudices which are every

where entertained against this thieving cosmopolite. Possessing scarcely one

redeeming quality, it has by its mischievous propensities caused the world to

unite in a wish for its extermination.

The Black Rat is omnivorous, nothing seeming to come amiss to its voracious

jaws--flesh, fowl or fish, and grain, fruit, nuts, vegetables, &c., whether raw

or cooked, being, indiscriminately devoured by it. It is very fond of plants

that contain much saccharine or oleaginous matter.

The favourite abodes of this species are barns or granaries, holes under

out-houses or cellars, and such like places; but it does not confine itself to

any particular locality. We have seen its burrows under cellars used for

keeping the winter's supply of sweet potatoes in Carolina, in dykes surrounding

rice-fields sometimes more than a mile from any dwelling, and it makes a home in

clefts of the rocks on parts of the Alleghany mountains, where it is very

abundant.

In the neighbourhood of the small streams which are the sources of the

Edisto river, we found a light-coloured variety, in far greater numbers than the

Black, and we have given three figures of them in our Plate. They were sent to

us alive, having been caught in the woods, not far from a mill-pond. We have

also observed the same variety in Charleston, and received specimens from Major

LECONTE, who obtained them in Georgia.

During the summer season, and in the autumn, many of these rats, as well as

the common or Norway rat, (Mus decumanus,) and the common mouse, (Mus musculus,)

leave their hiding places near or in the farmer's barns or hen-houses, and

retire to the woods and fields, to feed on various wild grasses, seeds, and

plants. We have observed Norway rats burrowing in banks and on the borders of

fields, far from any inhabited building; but when the winter season approaches

they again resort to their former haunts, and possibly invite an additional

party to join them. The Black Rat, however, lives in certain parts of the

country permanently in localities where there are no human habitations, keeping

in crevices and fissures in the rocks, under stones, or in hollow logs.

This species is by no means so great a pest, or so destructive, as the

brown or Norway rat, which has in many parts of the country either driven off or

exterminated it. The Black Rat, in consequence, has become quite rare, not only

in America but in Europe.

Like the Norway rat this species is found of eggs, young chickens, ducks,

&c., although its exploits in the poultry house are surpassed by the audacity

and voraciousness of the other.

We have occasionally observed barns and hen-houses that were infested by

the Black Rat, in which the eggs or young chickens remained unmolested for

months together; when, however, the Rats once had a taste of these delicacies,

they became as destructive as usual, and nothing could save the eggs or young

fowls but making the buildings rat-proof, or killing the plunderers.

The following information respecting this species has been politely

communicated to us by S. W. ROBERTS., Esq., civil engineer:--

"In April, 1831, when leading the exploring party which located the portage

railroad over the Alleghany mountains, in Pennsylvania, I found a multitude of

these animals living in the crevices of the silicious limestone rocks on the

Upper Conemaugh river, in Cambria county, where the large viaduct over that

stream now stands. The county was then a wilderness, and as soon as buildings

were put up the rats deserted the rocks, and established themselves in the

shanties, to our great annoyance; so that one of my assistants amused himself

shooting at them as he lay in bed early in the morning. They ate all our shoes,

whip-lashes, &c., and we never got rid of them until we left the place."

We presume that in this locality there is some favourite food, the seeds of

wild plants and grasses, as well as insects, lizards, (Salamandra,) &c., on

which these Rats generally feed. We are induced to believe that their range on

the Alleghanies is somewhat limited, as we have on various botanical excursions

explored these mountains at different points to an extent of seven hundred

miles, and although we saw them in the houses of the settlers, we never observed

any locality where they existed permanently in the woods, as they did according

to the above account.

The habits of this species do not differ very widely from those of the

brown or Norway rat. When it obtains possession of premises that remain

unoccupied for a few years, it becomes a nuisance by its rapid multiplication

and its voracious habits. We many years ago spent a few days with a Carolina

planter, who had not resided at his country seat for nearly a year. On our

arrival, we found the house infested by several hundreds of this species; they

kept up a constant squeaking during the whole night, and the smell from their

urine was exceedingly offensive.

The Black Rat, although capable of swimming, seems less fond of frequenting

the water than the brown rat. It is a more lively, and we think a more active,

species than the other; it runs with rapidity, and makes longer leaps; when

attacked, it shrieks and defends itself with its teeth, but we consider it more

helpless and less courageous than the brown or Norway rat.

It is generally believed that the Black Rat has to a considerable extent

been supplanted both in Europe and America by the Norway rat, which it is

asserted kills or devours it. We possess no positive facts to prove that this

is the case, but it is very probably true.

We have occasionally found both species existing on the same premises, and

have caught them on successive nights in the same traps; but we have invariably

found that where the Norway rat exists in any considerable numbers the present

species does not long remain. The Norway rat is not only a gross feeder, but is

bold and successful in its attacks on other animals and birds. We have known it

to destroy the domesticated rabbit by dozens; we have seen it dragging a living

frog from the banks of a pond; we were once witnesses to its devouring the young

of its own species, and we see no reason why it should not pursue the Black Rat

to the extremity of its burrow, and there seize and devour it. Be this as it

may, the latter is diminishing in number in proportion to the multiplication of

the other species, and as they are equally prolific and equally cunning, we

cannot account for its decrease on any other supposition than that it becomes

the prey of the more powerful and more voracious Norway rat.

The Black Rat brings forth young four or five times in a year; we have seen

from six to nine young in a nest, which was large and composed of leaves, hay,

decayed grasses, loose cotton, and rags of various kinds, picked up in the

vicinity.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION.

This species is constantly carried about in ships, and is found, although

very sparingly, in all our maritime cities. We have met with it occasionally in

nearly all the States of the Union. On some plantations in Carolina,

particularly in the upper country, it is the only species, and is very abundant.

We have, however, observed that in some places where it was very common a few

years ago, it has altogether disappeared, and has been succeeded by the Norway

rat. The Black Rat has been transported to every part of the world where men

carry on commerce by means of ships, as just mentioned.

GENERAL REMARKS.

PENNANT, KALM, LINNAEUS, PALLAS, DESMAREST, and other European writers,

seem disposed to consider America the Fatherland of this pest of the civilized

world. HARLAN adopted the same opinion, but BARTRAM, (if he was not

misunderstood by KALM,) did more than any other to perpetuate the error.

In the course of a mutual interchange of commodities, the inhabitants of

the Eastern and Western Continents have presented each other with several

unpleasant additions to their respective productions, especially among the

insect tribe.

We are willing to admit that the Hessian fly was not brought to America in

straw from Hanover, as we sought in vain for the insect in Germany; but we

contend that the Black Rat and the Norway rat, which are in the aggregate

greater nuisances, perhaps, than any other animals now found in our country,

were brought to America from the old world. There are strong evidences of the

existence of the Black Rat in Persia, long before the discovery of America, and

we have no proof that it was known in this country till many years after its

colonization. It is true, there were rats in our country which by the common

people might have been regarded as similar to those of Europe, but these have

now been proved to be of very different species. Besides, if the species

existed in the East from time immemorial, is it not more probable that it should

have been carried to Europe, and from thence to America, than that it should

have been originally indigenous to both continents? As an evidence of the

facility with which rats are transported from one country to another, we will

relate the following occurrence: A vessel had arrived in Charleston from some

English port, we believe Liverpool. She was freighted with a choice cargo of

the finest breeds of horses, homed cattle, sheep, &c., imported by several

planters of Carolina. A few pheasants (Phasianus colchicus) were also left on

board, and we were informed that several of the latter had been killed by a

singular looking set of rats that had become numerous on board of the ship. One

of them was caught and presented to us, and proved to be the Black Rat. Months

after the ship had left, we saw several of this species at the wharf where the

vessel had discharged her cargo, proving that after a long sea voyage they had

given the preference to terra firma, and like many other sailors, at the

clearing out of the ship had preferred remaining on shore.

We have seen several descriptions of rats that we think will eventually be

referred to some of the varieties of this species. The Mus Americanus of

GMELIN, Mus nigricans of RAFINESQUE, and several others, do not even appear to

be varieties; and we have little doubt that our light-coloured variety, if it

has not already a name, will soon be described by some naturalist who will

consider it new. To prevent any one from taking this unnecessary trouble, we

subjoin a short description of this variety, as observed in Carolina and

Georgia.

Whole upper surface, grayish-brown, tinged with yellow; light ash beneath;

bearing so strong a resemblance to the Norway rat, that without a close

examination it might be mistaken for it.

In shape, size, and character of the pelage, it does not differ from the

ordinary black specimens.

|